Diversity, Equity, Inclusivity & Accessibility (DEIA)

Department of Epidemiology

Education

The Centrality of DEIA in Epidemiology and Public Health

Diversity of thoughts and opinions is the foundation of scientific innovation and rigor in research which, in turn, promotes health for all. If diversity of thoughts and opinions serves as fodder for innovation and if such diversity stems from diverse lived experiences, then such diversity needs to be intentionally incorporated into research and education in an equitable, inclusive, and accessible manner.

Health equity is a key component of public health education and practice. As epidemiology researchers, educators, mentors, and trainees, we have an opportunity and responsibility to study how systemic disparities cause avoidable and preventable inequities in health outcomes, and to center health equity as a framework to guide our work within and outside of the classroom.

Key Concepts

Diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility: In our Department, we value diversity and strive to be inclusive and supportive of individuals of all ages, religions, veteran statuses, races, ethnicities, biological sex assigned at birth, sexual orientations, genders, socioeconomic statuses, and disabilities (physical, mental, social, developmental, or emotional). Equity ensures that the needs of all individuals are met, enabling all people to achieve the same level of success as their colleagues and classmates. Inclusion involves implementing ways to increase a sense of belonging for everyone in the Department, with a focus on those who are not in the majority or advantaged groups. Accessibility is ensuring that all people in our Department have equitable access to opportunity and education.

Microaggressions: Brief and subtle verbal and/or non-verbal denigrating messages directed towards individuals or communities from underrepresented populations that carry the weight of the offending party’s implicit bias, often below their own conscious awareness.

Health disparities and health equities: These definitions have evolved over time, but generally, differences in health among population groups are called health disparities. Health disparities that are deemed unfair or stemming from injustice (such economic, social, or environmental disadvantage) are called health inequities.

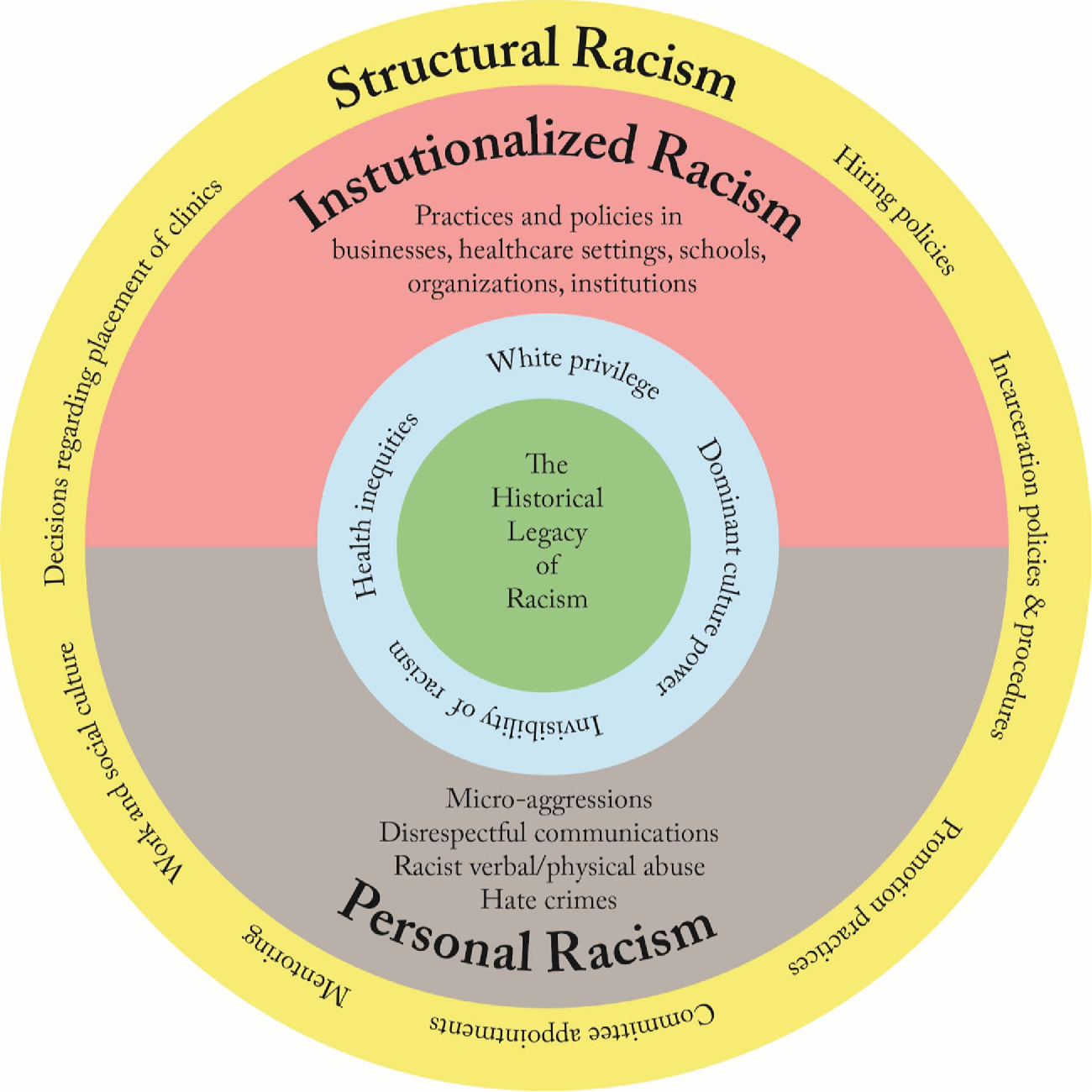

Systemic racism, structural racism, and institutional racism: Systemic and structural racism are forms of racism that are pervasively and deeply embedded in and throughout systems, laws, written or unwritten policies, entrenched practices, and established beliefs and attitudes that produce, condone, and perpetuate widespread unfair treatment of people of color. They reflect both ongoing and historical injustices. Although systemic racism and structural racism are often used interchangeably, they have somewhat different emphases.

Systemic racism emphasizes the involvement of whole systems, and often all systems—for example, political, legal, economic, health care, school, and criminal justice systems—including the structures that uphold the systems.

Structural racism emphasizes the role of the structures (laws, policies, institutional practices, and entrenched norms) that are the systems’ scaffolding. Because systemic racism includes structural racism, for brevity we often use systemic racism to refer to both; at times we use both for emphasis.

Institutional racism is sometimes used as a synonym for systemic or structural racism, as it captures the involvement of institutional systems and structures in race-based discrimination and oppression; it may also refer specifically to racism within a particular institution.

Cultural competence and cultural humility: Cultural competence is the ability to understand, communicate with, and effectively interact with people across cultures. Cultural humility goes beyond the concept of cultural competence to include a personal lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique, recognition of power dynamics and imbalances, a desire to fix those power imbalances and to develop partnerships with people and groups who advocate for others, and institutional accountability.

Assess Your Understanding of DEIA

The first step to researching and advancing health equity is educating yourself. How well do you understand these topics? Take our quiz to find out.

Epidemiology Health Equity Council

Who We Are

The CSPH Epidemiology Health Equity Council (HEC) is a committee focused on improving initiatives related to DEIA within our Department. We are made up of faculty, staff, and students within the Department of Epidemiology. Current members are Wei Perng, Associate Professor; Rebecca Conway, Associate Professor; Molly Lamb, Clinical Teaching Associate Professor; Kendra Young, Research Assistant Professor; Brianna Moore, Assistant Professor; Dorah Labatte, DrPH Student Representative; Celeste Connell, Staff Representative; Blair Weikel, PhD Student Representative; Johnna Bakalar, PhD Student Representative; and Alyssa Beck, PhD Student Representative.

If you are interested in collaborating with or joining the HEC, please email council chair Dr. Wei Perng.

Mission & Vision

The mission of the Epidemiology Health Equity Council (HEC) is to ensure diversity, equity, inclusivity, and accessibility within the Department of Epidemiology and the Colorado School of Public Health. We aim to identify and promote opportunities in public health research and practice for all people. Our vision is founded in the pursuit of an empathetic and inclusive academic environment that supports accessible education and impactful research, regardless of social identity and prior experiences, within the shared goal of optimizing population health.

HEC Newsletter Archives

Resources

- CSPH Land Acknowledgment

- CSPH Labor Acknowledgment (coming soon)

- CSPH Community Agreements

- JAMA Inclusive Language for Reporting Demographic and Clinical Characteristics*

- *This is one of many guides; many journals have their own requirements. These language nuances are changing and evolving.

- Utilization and conceptualization practices for race and ethnicity in epidemiologic research

- Rethinking Race and Ethnicity in Biomedical Research

- Declaration of Helsinki - revised to modernize research ethics standards

- Digital Accessibility Guide

Spring 2025 Research Spotlights

To Measure Diversity And Representation In Health Policy Research, Journals Should Adopt Personal Identity Disclosures

Co-author: Epidemiology PhD student Blair Weikel

Co-author: Epidemiology PhD student Blair Weikel

Epidemiology PhD student Blair Weikel co-authored an article in Health Affairs about the use of personal identity disclosures in medical journals, whereby authors state their personal and intersectional identities acknowledging the impact of potential biases held by investigative team members, and the role of structural racism. This disclosure system is based on existing Conflict of Interest policies, and if widely adopted, would create a system of public accountability for research team diversity and enable tracking of diversity and representation in publishing.

Social Determinants of Uncorrected Distance and Near Visual Impairment in an Older Adult Population

Co-author: Epidemiology faculty Dr. Ali Abraham

Co-author: Epidemiology faculty Dr. Ali Abraham

Epidemiology faculty member Dr. Ali Abraham co-authored a recently-published paper in Translational Vision Science and Technology titled, “Social determinants of uncorrected distance and near visual impairment in an older adult population.” Using data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, the authors found that individuals with lower educational attainment (<high school vs. >high school or college), no eye doctor, and government-based (vs. private) insurance are 1.5 to 2 times more likely to have uncorrected near vision impairment, defined as impairment in the ability to read close text or do close work easily corrected with appropriate reading glasses. These results point to gaps in vision health literacy and access to vision care as drivers of correctable vision disparities. Inclusive and equitable vision care means addressing evidence-based social drivers and designing and implementing interventions that can reduce correctable vision impairment in aging adults, particularly in vulnerable individuals who may be more likely to experience barriers to vision care access.

Economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on families of children with autism and other developmental disabilities

Co-author: Epidemiology faculty Dr. Carolyn DiGuiseppi

Co-author: Epidemiology faculty Dr. Carolyn DiGuiseppiEpidemiology faculty member Dr. Carolyn DiGuiseppi co-authored a paper in Frontiers of Psychiatry titled, “Economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on families of children with autism and other developmental disorders.” This study used data from the the Study to Explore Early Development (SEED), a multi-site case-control study of preschool children, to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parental employment and economic difficulties among families of children with autism or other developmental disorder, and in the general population. The study team found that families of children with autism, those of lower socioeconomic status, and those of minoritized racial and ethnic groups experienced lower work flexibility (e.g., less ability to transition to remote work), more employment reduction, and greater financial distress (e.g., more difficulty paying bills, greater fear of losing home) during the pandemic. Future research is required to assess where these impacts, which disproportionately affect vulnerable families, are sustained over time.